19 SEPTEMBER 2020 – 11:00 AM EDT

Umingmak: A dictator who brought democracy.

New biography offers a first-person look at a revolutionary era.

By Jim Bell former editor of Nunatsiak News, the official newspaper for Nunavut and Nunavik territory of Quebec.

In February 1967, Prime Minister Lester Pearson brought Stuart Milton Hodgson into his office to present the new commissioner of the Northwest Territories with his marching orders.

Pearson told the tough, charismatic labour leader that he wanted big results.

“In return, I will give you my full support,” Pearson said. “No one else in this country will have the kind of authority you will. Not even me.”

And so Hodgson, armed with dictatorial powers and the personal support of the prime minister, set out to ignite a revolution.

Jake Ootes, Hodgson’s former executive assistant, tells the story of how that happened in an intimate first-person account of those times, titled Umingmak: Stuart Hodgson and the Birth of the Modern Arctic.

Ootes writes in the first person, building his narrative through detailed anecdotes and personal observations, conveyed by long stretches of dialogue in which the people of that time talk to each other like characters in a work of fiction.

That means it’s definitely not the kind of tedious academic text that will put you to sleep in five minutes.

“I inject myself into the story everywhere, but it covers Hodgson as a character. It also covers the Northwest Territories and the Arctic as a character, because I felt it was important to get a picture of what the North was like in those days,” Ootes said in an interview with Nunatsiaq News.

In a note near the front of the book, Ootes explains why he uses terms like “Eskimos” and “Indians,” now widely regarded as offensive anachronisms. “While these words are now recognized as pejorative, they were commonly used in the North at that time.… The words Native, Aboriginal and Indigenous have all been similarly used in the context of the time.”

Hodgson, named “Umingmak” during an early visit to the High Arctic, was a left-leaning progressive. He worked many years as an organizer for the British Columbia branch of the International Woodworkers of America, a union that represented loggers and sawmill workers, and was also a founding member of the New Democratic Party in 1961.

Later, he moved closer to Lester Pearson’s Liberals. They appointed him to the N.W.T. territorial council in 1964, where he served as deputy commissioner. In 1967, he became a benevolent dictator, sometimes known as the “Emperor of the North.” When he moved to Yellowknife, he became the first commissioner to make their home in the North.

A dictator who brought democracy

In one of the great paradoxes of modern northern history, the appointed colonial dictator devoted himself to a decolonizing project, bringing modern democracy and lasting institutions to the North that continue to empower Indigenous people today.

“He definitely was dictatorial. He had that power that was given to him and he took full advantage of it. And thank goodness in many ways, because he had sensitivity to those people in the small communities,” Ootes said.

The newly created small communities, especially in the Eastern Arctic, suffered from extreme government neglect and incompetence. There were no local governments, no airstrips, no reliable telephone service, no garbage disposal, no CBC radio, and no reliable water and sewage service.

Stuart Hodgson with Atuat, the revered elder from Arctic Bay. (Photo by Jake Ootes)

Hodgson noticed all this on his first tour of the Eastern Arctic, which was largely conducted in the winter of 1969. On that 2,000-mile, 15-community trip, he travelled on a Twin Otter fitted with balloon tires so it could land on sea ice, due to the lack of permanent airstrips.

For example, he visited the Belcher Islands, where the federal government was supposed to have built a school at a place called North Camp, where most people lived in what is now Sanikiluaq.

But the captain of a ship carrying the building supplies couldn’t find North Camp, so he dumped the materials at a place called South Camp, about 50 miles away.

People were forced to move there to send their kids to school. The federal government built no housing, so 17 families lived in shacks and framed tents that in the winter were buried in snow.

At that time of Hodgson’s appointment in 1967, it was almost impossible for the Inuit of the Eastern Arctic to complain about such blundering negligence. The people of the N.W.T, including those who lived on the lands that later became Nunavut, were ruled directly from Ottawa by civil servants employed by the northern affairs branch of the Department of Northern Affairs and Natural Resources.

A new government emerges

But after Sept. 18, 1967, when Hodgson packed the entire territorial government, consisting of about 30 civil servants and himself, into two chartered aircraft and flew them to Yellowknife, all that changed.

Community members shovel out a sea-ice runway for Stuart Hodgson’s Twin Otter during a visit to Sanikiluaq in 1969. (Photo by Jake Ootes)

By the time Hodgson departed on April 26, 1979, that small group had grown: 2,845 civil servants worked for the Government of the Northwest Territories. Its budget grew from $14.5 million in 1967 to $282.1 million in 1979.

On his departure, Hodgson left behind a modern territorial government and an N.W.T. territorial council that had become a fully elected legislative assembly dominated by an Indigenous majority.

And on April 1, 1999, the Government of Nunavut inherited those institutions, giving the Inuit of Nunavut more power than almost any other Indigenous group living within Canada.

“It’s a story of transformation,” Ootes told Nunatsiaq News. “There was a genuine desire on Hodgson’s part and on the part of the territorial government to ensure that communities received the benefits of service.”

Many of those improved services came about through the rapid devolution of power from the federal government. Hodgson used his dictatorial influence to create a long list of new territorial departments and agencies, including separate departments for public works, personnel, education, justice, renewable resources, social services, and the N.W.T. Housing Corp.

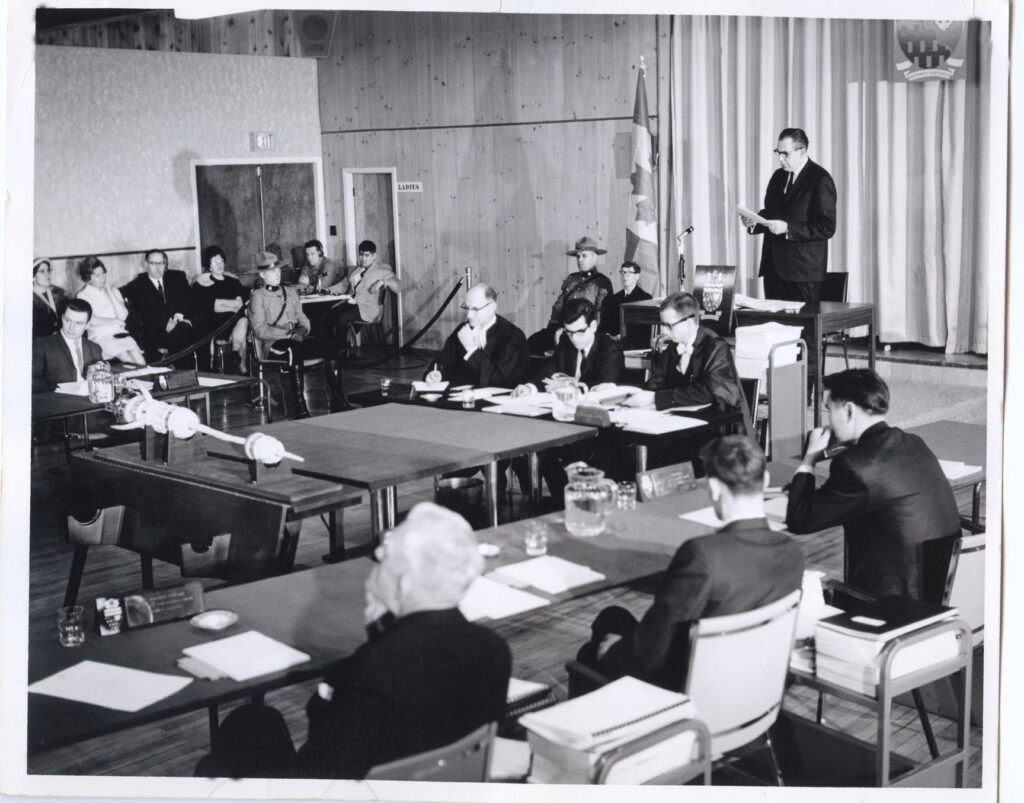

Stuart Hodgson speaks at an early meeting of the territorial council, the body that evolved into the legislative assemblies of Nunavut and the Northwest Territories. (Photo by Jake Ootes)

One of the most important was the Department of Local Government, the direct ancestor of Nunavut’s Department of Community and Government Services. It gave birth to what is now Nunavut’s system of hamlet councils, which Hodgson believed were essential for the development of democratic government in the territory.

History has proved him right. Nunavut’s municipal governments still serve as a political training ground for people who start off as hamlet councillors and mayors, then go on to serve as MLAs and cabinet ministers.

“Hodgson spent years going around to communities and setting up a system whereby local people could take over the positions, both administratively and politically in the communities. That is what in my mind got rid of colonialism,” Ootes said.

“To me, the Northwest Territories government was not a colonial government. It was there to get rid of colonialism,” Ootes said.

Grand gestures, media publicity

Hodgson was known for grand gestures and for his constant courting of news reporters from outlets such as the Canadian Press and the New York Times and Time, as well as tiny regional newspapers like Nunatsiaq News.

To help Nunatsiaq News, then owned by editor-publisher Monica Connolly, Hodgson decreed in 1975 that all GNWT print advertising in that paper be published in Inuktitut as well as in English. This ensured the struggling newspaper’s survival.

Hodgson also created the first Arctic Winter Games in 1970, attended by Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, and he hosted visits to the North by Queen Elizabeth II and the Prince of Wales.

He ordered the creation of the famous interpreter corps, a trained group of Inuit-language interpreters and hired people like Peter Irniq, John Amagoalik and James Arvaluk to serve as information officers for the new government.

“It was a 12-year transformational period. It was incredible how fast it started to happen. After that time, it was really in the hands of the people themselves,” Ootes said.

Jake Ootes

Umingmak: Stuart Hodgson and the Birth of the Modern Arctic

ISBN 978-1-7770101-0-2 (softcover)

ISBN 978-1-7770101-1-9 (html)

6″ x 9″

Publication date: May 2020

C$29.95, published by Tidewater Press

The book is available from Indigo and Amazon.

Note: Some of the figures and dates in this article are sourced from a book titled Whose North? Political Change, Political Development and Self-Government in the Northwest Territories by Mark O. Dickerson.